The sole is the guardian that shields the sensitive structures of the hoof from contact with the outside world. Acting as the primary barrier against ground surface trauma, it is designed to handle concussion naturally; however, it seems that this once efficient protector has become one of the most abused structures of a horse's anatomy.

While the sole itself can grow quickly, it is the formation of callous that creates the necessary cushioning effect and that develops slowly.

Using healthy hooves from domestic horses as the standard, sole thickness normally is about 3/8 inch, with a uniformed callous extending to the underside of the lateral cartilages and the coffin bone.

Seen in a standing horse, a naturally shaped hoof would also have an arch to reflect the coffin bone's position at the front half of the foot, with the lateral cartilages forming the underpinning for the back half. This type of configuration allows for flexibility of movement, which enables the foot to effectively dissipate the shock of impact. And, while a stone bruise can happen as quickly as stepping on a rock, the amount of force placed on a thin-soled foot will have a direct effect on its susceptibility to harmful trauma in general.

Causes For Thin Soles

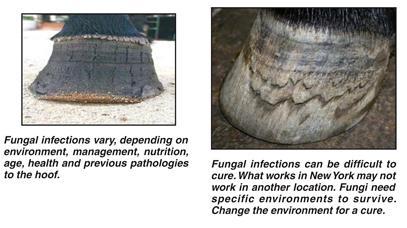

Michael Wildenstein, the head of the farrier's program at the College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University, says a variety of conditions that span the gamut from genetics, nutrition, management, environment, aging and past pathologies can bring on thin soles.

"Nothing is ever static when it comes to hoof health," says the certified journeyman farrier, who is also a Fellow with honors of the Worshipful Company of Farriers of Great Britain as well as a member of the International Horseshoeing Hall Of Fame. "Take an otherwise fit horse whose genetic lineage points to his having thin soles, then the likelihood is that he will as well. On the other hand, if a horse were to have no genetic predisposition, but is nutritionally compromised, the result could be the same."

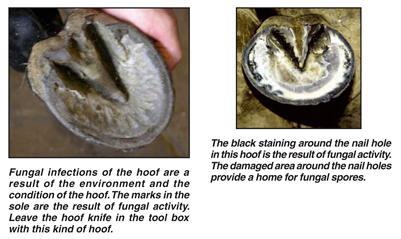

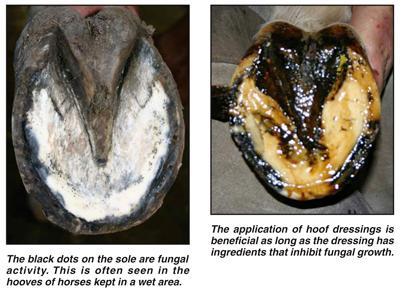

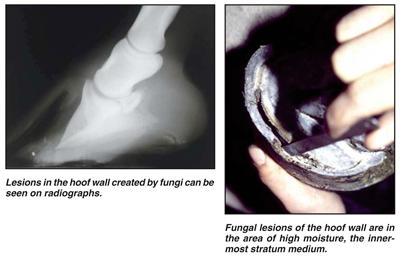

Regarding the theory that there is a direct link between fungal disease and thin soles, whether due to health or trauma, he notes that fungal spores are everywhere. However, these are usually no cause for concern unless there is a systemic imbalance, topped by an external disruption, as in the case of the horse who is nutritionally deficient and then suffers a minor sole bruise.

"Because his immune system already is depressed and because fungi are opportunistic in nature, invasion will meet with little resistance as they overwhelm the healthy tissues, eating them as they grow," he says.

From a trimming perspective, he notes that the sole can be easily misread, which can contribute to the problem. He says it can be difficult to distinguish between what is healthy and needs to be preserved and false sole, which should be removed. Some sole that is shedding should be left alone so that new sole underneath can mature, but other sole that is shedding may need to be removed due to fungal infection.

Vertical Depth Is A Key

Dave Birdsall, another member of the International Horseshoeing Hall Of Fame, brings over 40 years of experience to the profession. He stresses the importance of getting the right vertical depth, from the coronary band to the apex of the frog. He also says simple thumb pressure is a good way to check for thin soles. "If there is movement, there is sensitivity," says the Water Mill, N.Y. shoer.

Jeff Myrick, a certified journeyman farrier with over 20 years of experience, agrees. He notes that California hoof researcher Mike Savoldi has shown that reading sole concavity — or the lack of it — and paying particular attention to the vertical depth of the hoof are primary concerns for anyone involved in hoof care.

Myrick points out that these issues are as relevant for hoof trimmers as they are for horseshoers.

"A thin sole may be very concave or very flat," says the Sandgate, Vt., farrier. "It is usually the case that a concave foot with a thin sole will soon become a flat-soled foot as the structure of the foot fails. The outer wall will spread, followed by losing its symmetrical strength and vertical depth."

Too Much Knife Work

Myrick says farrier error can contribute to the problem.

"Perhaps the sole lost its strength because of the athletic overuse of the hoof knife," he says. "I remember a rash of thin-soled horses who began to appear right after I bought a hoof-knife buffing system. My knife was so exquisitely sharp that I dove into feet like a hyper-caffeinated beaver. This particular problem is still common enough to point it out.

"I over trimmed many soles in search of breakover and other more mythical designs. Be wary; a well-trimmed and routinely shod foot should require almost no knife work after the foot is in balance; it will grow and shed on its own. If it is not, re-evaluate your trim. You cannot create lasting solar concavity by the spastic use of your hoof knife."

Toughening Up The Sole

As for treatment, Birdsall is a believer in packing the sole with pine tar and oakum over which he will use a leather pad when possible.

"I prefer leather because it offers protection at the same time enabling the foot to breathe," he says.

He also says using a crème brule torch to lightly sear the sole is an effective way to dry it out before applying the packing and pad. However, he warns that the torch should be used with great care.

Birdsall says Venice turpentine is very effective at toughening up the sole. In addition, he came up with his own remedy, Farriers Barrier, "which I developed out of necessity. I wanted to provide farriers and owners alike with an all-in-one topical treatment that would keep tissues healthy and protect the foot against excessive dryness and moisture."

For the convex foot, with a dropped sole, Birdsall has had good success using a heart bar shoe and rim pad for additional protection.

Wildenstein and Myrick endorse Venice turpentine as well, touting it as an age-old cure and the first thing to reach for, with pine tar, tea tree oil and eucalyptus oil having nearly equal results.

"These products are moderately priced and are as effective as anything else in the long run," says Myrick. "If fungal infection is suspected, nothing will out perform Venice turpentine," he says. "In severe cases I have used both extremely strong iodine (Hoof Freeze) and Venice turpentine as short term therapies. A seated-out and wider webbed shoe in conjunction with a leather pad is a good way to get the horse back in the show ring."

Wildenstein endorses White Lightning as an anti-fungal treatment that does not harm healthy tissues while it is used. A stabilized chlorine solution, when combined with equal amounts of a mild acid, such as white vinegar, will generate a chemical reaction resulting in chlorine dioxide (ClO2). Used in conjunction with a tightly wrapped plastic bag and a fitted protective boot, the gas penetrates every crack and crevice of the sole, neutralizing the fungus. Wildenstein recommends a bi-weekly treatment schedule until the tissues have regenerated.

The Role Of Pads

He believes pads should be viewed as temporary treatments whenever possible. Like Birdsall, he prefers leather for the same reasons, although he does acknowledge that synthetics have their place, especially when it comes to providing additional protection against concussion.

"And they last longer," Wildenstein adds. However, he cautions against overdoing it. "Regardless of what pad best suits the situation, be careful not to create a cycle of pad dependency."

Maintaining the integrity of the sole is key to lowering the risk of bruising and lameness.

"Remember that a horse with no vertical depth is in no need of breakover enhancement," says Myrick. "He needs protection. Leave the toe. First gain hoof mass, then you can start to carve it away to suit your philosophy."