Understand What You Need To Charge

What can you charge?

It’s a question that farriers commonly ask and one that Adam Wynbrandt hears often. His response?

“I tell them, ‘Well, no, the question is, what do you need to charge?’” says Wynbrandt, who has 2 decades of farriery experience and owns The Horseshoe Barn in Sacramento, Calif.

Even veteran farriers struggle with finding a winning formula, but Wynbrandt finds there’s a common mistake.

“Most farriers work off of gross income rather than net,” he says. “What’s the difference? If you just did six horses for $600, that’s your gross income. That’s all your money. In reality, you have costs, expenses and taxes. The amount of money you have after those expenditures is your net income.”

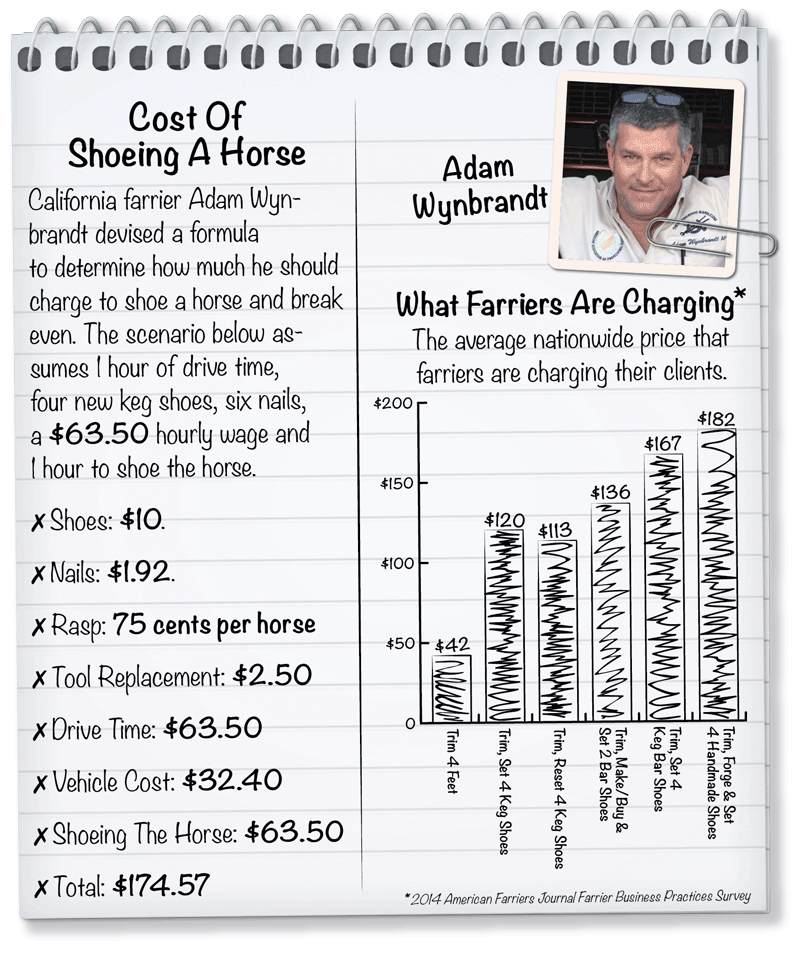

The Cost Of Shoeing A Horse

According to the latest Farrier Business Practices survey conducted by American Farriers Journal, the average nationwide price for trimming four hooves and applying four keg shoes is $120.19. The average charge for trimming and resetting four keg shoes is $113.36. Trim-only prices average $42.06.

It’s critical that you cover the replacement costs for your tools and equipment.

Reducing your drive time and shoeing more horses at one location puts more money in your pocket.

Your business should have a ratio of about 70% gross income vs. about 30% costs.

Those prices might not work for you and your situation, though. Wynbrandt, for instance, shoes horses in California, which has a higher cost of living than most states. Then again, the prices might indeed fit your lifestyle, you just need to budget your income more efficiently. That’s where Wynbrandt found himself just 2 years into his career. Wynbrandt’s practice was thriving, but he was in for a rude awakening.

“I went in to get my taxes done,” he recalls. “When the accountant told me what I owed, I fainted. It was always a stressful time for me to get my taxes done. So I had to come up with a plan.”

The easiest way to calculate expenses, Wynbrandt says, is to figure each stop as a full shoeing — new shoes on the front and hinds. Plugging in the numbers, he details his expenses.

- Shoes: $5 a pair for a total of $10.

- Nails: 8 cents per nail; six nails per foot for a total of $1.92.

- Rasp: Over the course of a 5-day workweek, Wynbrandt goes through one $30 rasp to trim 40 horses. Dividing the cost of the rasp by the number of horses, he estimates it costs 75 cents per horse to buy a new rasp.

- Replacement costs: He recommends setting aside $2.50 from every full shoeing to cover wear and tear on tools and equipment.

Adding up the above expenses, Wynbrandt finds that it costs him $15.17 in materials.

Your Hourly Wage

Although many farriers find it difficult — both from a financial and a scheduling standpoint — to take some time off, Wynbrandt builds it into his formula when figuring out an hourly wage.

“There are 52 weeks in a year and you’re going to take a 2-week vacation,” he says. “It doesn’t matter. We’re going to calculate your wage into that.”

You need to do more horses at each stop …

As a result, Wynbrandt calculates total hours based on 8 hours a day, 5 days a week and 50 weeks a year.

“It’s going to be 2,000 hours a year that you will work,” he says. “I know we’ll be short, but I’m covering a baseline. If you’re faster at shoeing horses, you’ll get done in less than 8 hours. This is the easier way of doing it.”

Once Wynbrandt figured out the number of hours he would be working, he wanted to determine an annual salary target.

“How much do you want to make a year — net?” he asks. “Sometimes, people tell me they want to make $1 million. That’s not realistic. I picked $100,000. That’s what I wanted to make to pay for my daily expenses.”

As Wynbrandt alluded to earlier, the key word to consider is “net.” That means he had to earn more than $100,000 a year gross to achieve his goal because taxes, insurance and retirement drops him below his target.

Earning $100,000-plus a year put Wynbrandt in the 10% tax bracket, or about $10,000 a year to Uncle Sam. Insurance can cost you more, especially if you have dependents. Yet, many farriers forgo insurance.

“It’s pretty sad,” he says. “It’s tough and it’s a biggie, but it can be done. Personally, I paid $1,000 a month between my two kids. That’s $12,000 a year.”

If insurance isn’t a priority for many farriers, contributing to retirement accounts often has less appeal. Yet, now is exactly the time to take advantage of the opportunity to begin saving for your golden years.

“If you put $5,500 a year into a Roth IRA, you pay taxes with your contributions,” Wynbrandt explains. “After you reach 62, it’s tax free. If you draw it out at age 65, you would have paid $192,500 into the account and the return on interest would be $1.6 million. Can you imagine if you and your spouse had a Roth? That’s $3 million. It’s crazy.”

After figuring out that he wanted a net income of $100,000, and pay $10,000 a year for taxes, $12,000 a year in health insurance and $5,500 for retirement, Wynbrandt actually wanted to target $127,000 as his net income goal. That means his hourly wage is $63.50.

Vehicle Costs

Your vehicle is the most expensive tool that you own. Given the amount of wear and tear you will put it through, it’s also among the most depreciable.

You can replenish some depreciation by claiming mileage or fuel receipts through your annual tax return.

“I took mileage because I was really bad at keeping receipts,” Wynbrandt confesses. “It was easier when I started the year, I wrote my mileage in. On the last day of the year, I wrote my mileage in my other book and that was that.”

The Internal Revenue Service permits 54 cents a mile, but it doesn’t completely cover your costs.

You have to live off the net income and not the gross …

“Assuming most of us drive 60 miles an hour most of the time, and you get 54 cents a mile from the IRS,” he says, “you would have to charge $32.40 for every hour that you are driving in your vehicle to break even.”

When choosing the mileage route, you won’t be permitted to track such costs as tire replacement and oil changes.

“When you take mileage, that’s what you get,” Wynbrandt says. “Now, if you have to get an engine replaced, or something catastrophic, there are ways around that with your accountant. You can deduct it. A good tax guy can find it.”

That’s not the only vehicle-related charge you should be levying.

“You need to be getting paid for your time while driving your truck,” Wynbrandt says. “It’s part of your day. If you’re on an 8-hour day, you’re actually getting paid to drive.”

So, given the formula that Wynbrandt follows, how much does he charge to shoe one horse?

- Drive time: A half-hour drive to the barn and a half-hour back will amount to his hourly wage of $63.50.

- Vehicle cost: $32.40 for 1 hour of drive time.

- Shoeing supplies: $15.17 to cover a full set of shoes and costs of his tools.

- Shoeing the horse: It generally takes Wynbrandt an hour to shoe a horse. His hourly wage is $63.50.

- Shoeing bill: $176.07 is charged to the client.

“That’s not bad money,” he says. “That’s to break even.”

After working on his system for several years, Wynbrandt found that cutting down the driving time meant a healthier bottom line.

“If you have the opportunity, you need to work in a tight demographic area,” he suggests. “After running a number of scenarios, I found that just the driving time was changing my shoeings by $20. That’s $20 you can be putting in your pocket.

“You need to do more horses at each stop. You don’t make as much money when you do one or two horses at one stop.”

It’s worth repeating that these figures are based on Wynbrandt’s business in California. The cost of shoeing supplies, insurance and other expenses might be different where you practice.

The ratio you’re looking for is 30% cost and 70% gross income …

You can plug in your own numbers by using an Excel worksheet that was developed by Bob Schantz, a Hall Of Fame farrier and owner of Spanish Lake Blacksmith Shop in Foristell, Mo. You can download the worksheet by visiting Farrier Product Distribution’s website (farrierproducts.com/farrierpricingworksheet.html). American and Canadian Associations of Professional Farriers members also can download it from its organization’s website (professionalfarriers.com).

Analyze Your Business

Many farriers get caught up in the practical side of farriery. They don’t pay enough attention to the business side of their practice and find themselves in a financial pickle.

“It’s important to analyze your business,” Wynbrandt says. “A lot of us don’t do it. We just shoe. We give the money to our spouse and then it’s gone. You have to run your business as a business. You have to live off the net and not the gross.”

It’s imperative that you analyze your business at least twice a year to ensure that you are on the right track.

“You should see your accountant in June and again at the end of the year when you get your taxes done,” Wynbrandt says. “The accountant can tell you that you need to buy something or adjust your finances to avoid paying more taxes than necessary. I pay my tax guy a lot of money so I never get audited. I don’t want the trouble.”

It’s important for the financial health of your family and your business that you can recognize when adjustments need to be made.

“I would overanalyze it,” he says. “I ran it as a business. The ratio you’re looking for in a business is about 30% cost and about 70% gross income. So, when you look at what it costs to do your business, if it’s over 40%, you have to raise your rates. If you’re comfortable living on that, that’s fine. It’s just a pretty bad ratio when you exceed 30%.”