American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

The following article is based on Dr. Jennifer Gill and Chuck York's presentation at the 2018 International Hoof-Care Summit. To watch the presentation, click here.

Although some would argue that going barefoot is more natural for the horse in the long run, the fact remains that barefoot horses still face many of the same health concerns that shod horses do — and perhaps are at greater risk for developing complications from walking on man-made or rough terrains. Yet when a client insists that their horse is better off barefoot, what can a farrier do?

Years ago, there were no alternatives to traditional horseshoes. Now, farriers can recommend nontraditional solutions to owners who would rather their horses go barefoot. One of these solutions is the hoof boot. The use of hoof boots to protect the barefoot horse was recently made the focus of two studies conducted at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Ky.

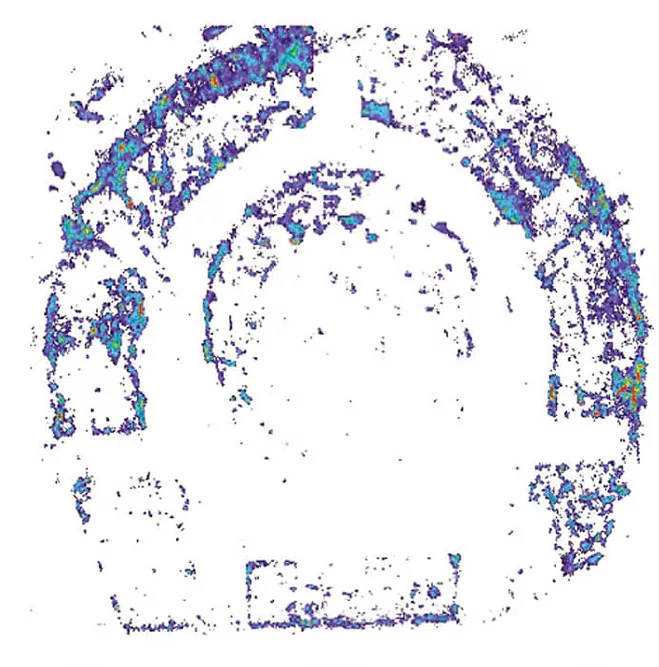

In 2017, Dr. Jennifer Gill, assistant professor of equine science in the university’s Agricultural Equestrian Unit, and undergraduate student Tabatha Stratton researched the potential benefits hoof boots can have for barefoot horses. To examine how…