Pictured Above: Tim Shannon (right) reviews radiographs with a vet and adds relevant information. Photo: Tim Shannon

Farrier Takeaways

- Any limitations in your skill set and knowledge base may require you to recommend another farrier for the case.

- Be prepared for the initial meeting with a veterinary colleague.

- Keep communication going on the progress of the horse.

There are many equine professionals that you will work with throughout your career. One of the most important relationships you can build is with equine veterinarians. Together, farriers and vets develop solutions to help the horse. Both need to understand their respective roles to keep the horse’s health above all else — especially egos.

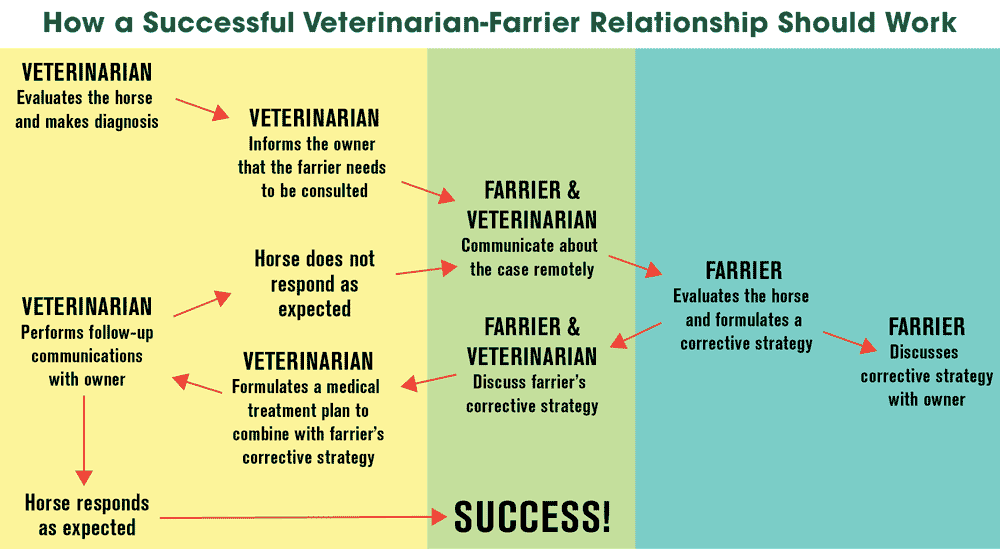

There will be times that you will encounter vets who are difficult to work with. However, relationships are two-way streets. Here is how I do my part as the farrier to build good relationships with vets in lameness cases. The flowchart below gives a visual depiction of how I think the team should progress on a case.

Before the First Encounter

Farriers typically enter lameness situations in two different ways. One might be when working on a horse and we see some issues with how the horse is moving and we let the client know that we’re going to need to get a vet involved, so we kind of have an idea of the way things are going. Or a client or vet will get a hold of us and inform us of the vet’s assessment.

Take that time before the encounter to get up to speed on the diagnosis, understand what you’re going to be working on and make sure you avail yourself to the current protocols. Then find out a little bit about the diagnostics of the case. That way, you can be conversant and have some of the same language. When the vet talks about osteophytes on a bone or lesions on a tendon, you know what the vet is talking about. It is important to understand the basics of diagnostics and the treatment protocols that might be coming from the vet’s point of view. This is going to figure in later, when we work on a shoeing protocol. The treatment plan and the shoeing protocol have to come together.

Review shoeing protocols for what you think is going to be the diagnosis so you have those in your head before the conversation. That way, the conversation moves faster and professionally.

This flowchart demonstrates a logical and respectful process for a veterinarian and farrier to work together on a lameness case. Note how the responsibilities of each party are clearly defined with each step. Illustration: Tim Shannon and Bob Grisel

First Encounter

I want to review diagnostics and modalities when getting together initially with the vet. You’re going to review what the vet went over to come up with a diagnosis. This is where you can add relevant clinical information you possess on the horse — something in the history the vet might not know about.

Next, review the biomechanical goals rather than a prescription for a shoe. Figure out what we need to make this horse move better or support something better in the next interim. Review those goals, then get a prognosis. Where is this going to go? Is this a laminitic horse that your goal is to be pasture sound? Or is this a performance horse that needs to compete? We need to know where it’s going to go.

I’m a fan of developing a Plan B. In many lameness cases, things don’t follow a linear route. You need to articulate what the next plan is going to be, that way you can notice the sign posts when they start showing up, when to implement Plan B, and everybody is on board ahead of time.

Maintaining the Relationship

Let’s assume that as the farrier, I have applied the necessary footcare protocol. Both farrier and veterinarian need to continue to share information, especially as the case progresses. Have your opinion respected and listen to the partner in the relationship. Are things moving along? When I come back, I’m going to reassess the horse, reshoe the horse and shoot off an email or text message letting the vet know what’s going on and where we are with the horse’s recovery.

When there are changes, those need to be spoken about to each other. The vet might come in for a recheck and see a change. The vet is going to have to let me know. We’ve got to keep up on the changes and we need to know those changes because we need to know when to implement Plan B. A lot of these diseases are dynamic and you’re going to be changing protocols and you must be aware of them.

Limitations in Skill

This is going to happen on both sides of the equation. Early in my career, I recognized the limitations of my skill and knowledge. With a particular case, I informed the vet that it would be best to bring in a more knowledgeable and skilled farrier. I only asked that I be allowed to be there while that other farrier is working on the horse. That way, I could learn. It was a pivotal point in my career. But you need to recognize what your knowledge base is and own it, but also know what you don’t know.

You will never know everything about hoof care. I continue to grow and learn. For example, I grow from learning diagnostics and how to help joints by conferring with veterinarians.

When to Exit the Relationship

I find the main reason of failure comes from a lack of communication. You must respect each other and talk to each other. When that breaks down, we’ve lost the groundwork. I’m not aware of what’s going on, and the vet doesn’t know what’s going on from my end. Because of this, our patient will start to falter. We don’t want to lose ground on the patient. It is best to exit these situations professionally for the betterment of the horse.