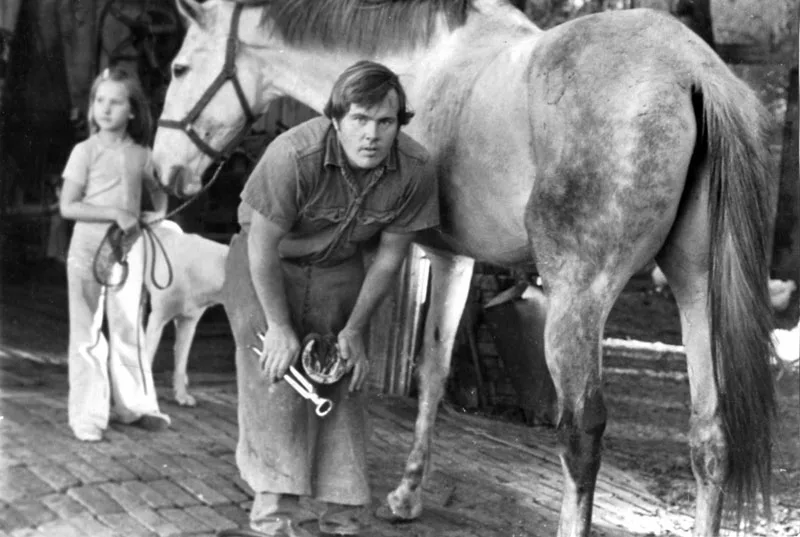

Pictured Above: Shoeing backyard horses in the early 1970s, Ray Nager believed horseshoeing is a way to make a good living, providing you have the talent and energy to run your own business.

Started Shoeing in High School

While Ray Nager spent 26 years shoeing horses on the racetrack, he started learning the craft while still in high school. Now retired in Lakeland, Fla., probably the most famous horse the 78-year-old farrier ever worked with was Spend A Buck, the winner of the 1985 Kentucky Derby.

Although I’m still in good health at 78 years of age, I wouldn’t like to go back to earning a living shoeing horses, as it can be a back-breaking job.

It can also be a dangerous job as I’ve suffered many a broken bone at the hands of a fractious horse or a careless horse handler. I’ve been stomped on, bit, run over and kicked with both barrels out through the side of a corner stall. Like many farriers, my list of nasty accidents is quite lengthy.

Looking back over the early days of my career, I was ornery enough and arrogant enough to somehow fill the bill as a farrier. That being said, horseshoeing was and still is a way to make a good living if you have the talent and energy to run your own business. One important skill you need to succeed is knowing how to get along with both the client and the client’s horses.

How to Be a Horseshoer

The most important aspect of the horseshoeing trade is learning the job in its entirety. I still remember my father’s admonition: “Son, whatever you choose to do in life, be the best.” That’s what I’ve always tried to do.

Early on in my horseshoeing career, I was told by a client, Nelson Zambito, “Ray, I like you as a person, you have a nice way about you and you’re good with a horse. I’d like for you to work for me at the track.” At that time, I was trimming Thoroughbreds at his farm.

To succeed, you need to know how to get along with the client and the client’s horses…

When I asked why, Zambito told me, “You need to learn how to shoe a horse.” I quickly explained that I already knew how to shoe a horse. I had started learning the craft in 1958 as a junior in high school.

Nelson went on to explain that, “Ray, it takes you almost 20 minutes to trim a horse, and the shoers at the track can trim and shoe a horse in that amount of time.”

I was dumfounded. So when I asked Zambito what I needed to do, he said, “Show up at the track Saturday morning and I’ll introduce you to the gang.”

I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for, but I told him I’d be there. The year was 1964, and this was when my true horseshoeing education really started.

Working in his shop, Ray Nager remembers his father’s advice that whatever you choose to do in life, always be the best.

I’d always been one who was willing to study, especially when I had a special interest in the topic. And I loved horses and I loved working for myself.

I had spent most nights during the previous half dozen years going to bed with a book to read. I studied the anatomy and physiology of the horse, the way a horse travels and equine diseases. After I started at the racetrack, I added books on metallurgy, tool making and lameness to my nightly reading list.

From 1964 to 1968, I showed up at the Tampa track’s blacksmith shop every morning at 8 a.m. Monday through Friday, along with some Saturday mornings. Working with other farriers, we would forge shoeing hammers, nippers, clinchers, tongs and whatever else we’d like. Most mornings, we’d go to the backstretch track barns and shoe until noon.

For your own sake, for your client’s sake and for the horses you shoe, education is a life-long endeavor…

In fact, I carried one blacksmith’s tools free for 3 years, as it was all part of my education. I did whatever was asked of me.

I reserved the afternoons for myself, as I was busy with my own off-track footcare customers.

I took the horseshoeing union test in 1968 at Hialeah Race track in Miami, but I didn’t pass the exam. Members of the examining panel told me I needed just a little more finesse.

When I asked what I needed to do, they told me to build two or three pairs of shoes every day and come back the following year to try again. I took their advice, making three pairs of shoes every day — except Sunday— for a year, forged from bar stock, hand swedged in the shoe dies that I had made, punched, toed and forge-welded as if they were bar shoes.

When I returned to Hialeah in January of 1969 to retake the test, the panel of five horseshoers looked at my shoes and asked what I had done to improve so much. After my year of intensive practice, they told me that I could forge shoes better than any of them could.

Needless to say, I passed my exam. I was now a bonafide member of the International Union of Journeyman Horseshoers (IUJH) of the United States and Canada. I later went on to shoe Spend A Buck, a horse that also won the Kentucky Derby.

Strive to Be the Best

In 1977, another farrier, Lee Tolerton, asked if I might come to the Florida State Fair and compete in the event’s first shoeing contest. I told him the other competing horseshoers would not want me to compete, which he thought was nonsense on my part.

After winning all three state fair contests that year, including the eagle eye and handmade shoe contest, I was politely asked not to return for the following year’s contest.

My basic philosophy has always been if you want to be the best, then take the necessary measures to earn it. For your own sake, for your client’s sake and for the horses you shoe, education is a life-long endeavor if you want to reach your full potential. The resources are out there, so do whatever it takes to succeed.

Taking the Journeymen’s

Horseshoers Test

Following a normal shoeing apprenticeship on the racetrack that lasted 5 years, a shoer could apply to take the International Union of Journeymen Horseshoers (IUJH) test that is governed by the local union.

Although I apprenticed in Tampa’s Sunshine Park (now Tampa Bay Downs), the local union was based in Miami at Hialeah Race Track. That southeastern Florida union was the third oldest horseshoeing local in the country.

Before you could take the IUJH exam, you needed a letter of recommendation or preferably a union member who would vouch for your character. The nine-member examining board consisted of five IUJH horseshoers, one veterinarian, a state racing steward, an owner and trainer.

270 Minutes of Shoeing Agony

The exam was 4 ½ hours long, with no grace period. You had to show up at the track on the morning of your scheduled test with your tools, anvil and fire. I was invited to use one of the forges in track shop, as you did not automatically presume you could use another man’s tools, forge or anvil without permission.

Starting at one of the backstretch barns, my test began with pulling the shoes and trimming the feet of one of the track’s lead horses provided by one of the blacksmiths. You then made a pattern of all four feet on the freshly trimmed horse with training plates.

The outside heels of the two front shoes were marked with a punch, as these would serve as your patterns for later building a pair of bar shoes. They needed to fit like wall paper on the wall — not too long or too short; not wider or narrower than any place on the shoe.

Back in the track shop, you lit the forge and proceeded to make the two front bar shoes from suitable bar stock. A medium shoe size was a #5 and required 11 inches of steel to make.

Those 32 holes all had to perfectly fit a number 3 ½ race nail…

Shoe sizes started with a #3 and ended with a #7. A pony would normally wear a size #6 or #7 shoe. A size #3 shoe needed 10 inches of steel and a #7 shoe required 12 inches of steel. Every size increased by ½ inch of steel to forge the shoe.

If a horse wore a #5 shoe that required 11 inches of steel, you needed to cut 13 ½ inches, providing an extra 2 ½ inches for the bar area. You marked the center and swedged the shoe 10 ½ inches in the training plate die you had made earlier. The steel was swedged with a 4-pound hammer whose head had been annealed (softened) so it would not damage your shoe die.

Next, you shaped the bars that had been cut for both the front and hind shoes. The hind shoes were swedged over their entire length except for the heel areas. At least 1 inch of steel on both sides of the bar was left unswedged so you could build a block-heeled shoe or a block and sticker. Both were required in the examination.

The swedged bars were turned with a wooden mallet to fit the patterns you had made for the front and hind shoes from the pony you had trimmed earlier. The front bar shoe patterns had been traced on a steel plate for easy reference.

After welding the bars in the front shoes and forging the hind shoes with pre-made block and stickers, spring steel toes cleats were sweated into all four shoes with pieces of copper and borax. After wire brushing and cleaning these shoes, four holes on each side of each branch of each shoe were punched. Those 32 holes all of which had to perfectly fit a number 3 ½ race nail.

Time for Shoe Inspection

It was now time to hand over the shoes to the panel of five horseshoers for inspection. All nail holes had to be the right size and in the proper location. No hammer marks were allowed on either the front or the back of the shoes. These handmade shoes had to be clean and look as good as factory-made shoes.

After the shoes were inspected, you went back to the barn, used the four shoes you had made earlier and shod the previously-trimmed track’s lead horse. The five union shoers judged your ability on how the horse was handled, whether the feet were trimmed properly and at the correct angle, the shoes were the proper length and nails were placed properly and driven at the proper height. They also checked your clinches and dressing of the feet.

Prior to shoeing, the bar shoes were placed on each foot. Both shoes had to fit perfectly, as they could not be off even 1/8 of an inch — again not too long, not too short, not too wide or too narrow. They had to fit like wallpaper on the wall.

Now came the conclusion of your examination. Remember the two bar shoes you made earlier that morning? Returning to the blacksmith shop, one of the horseshoers took one of your bar shoes and stood it vertically on the anvil. Taking a sledge hammer, he would try to break your weld. If the shoe gave way to the repeated blows and your weld broke, you failed the exam.

The other bar shoe and hind shoes you had forged were kept on file by the union. Once you passed the exam, they voted to see if they wanted you as a IUJH member.

The IUJH test was a big deal and certainly a serious and thorough exam. You were also questioned on your knowledge of the horse and its anatomy. If one aspired to this level of horseshoeing expertise, you had to study hard and put everything you knew into practice.

Horseshoers Were the Oldest

Union in North America

Established in 1874, the International Union of Journeymen Horseshoers (IUJH) is the oldest American union in continuous existence within the United States. This is true even though the union was dramatically expanded and was renamed the International Union of Journeymen and Allied Trades (IUJAT) in 2003.

Thanks to a merger among several unions with workers in non-related trades, the union’s membership grew dramatically and today includes thousands of service workers, industrial tradesmen and healthcare workers.

The Heavy Horse Union

During the late 1800s, the IUJH was known as the Heavy Horse Union. Thousands of members shod the draft horses that served as the real horsepower behind the nation’s transportation, construction and agriculture industries.

In 1893, the union became affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, which later became the huge AFL-CIO organization that still represents many unions today. By 1928, there were over 300 local horseshoer union groups around the country.

In the early days of the 20th century, the union was closely associated with the Teamsters, whose members represented the professional drivers of horse-drawn vehicles. The working relationship between these two unions was so close that no Teamster union member would drive any horses that did not bear a IUJH logo on its shoes.

But as horse numbers declined after World War I due to new developments in farm and transportation mechanization, the Teamsters traded their horses for trucks. They soon became one of the largest unions in America.

While IUJH membership numbers decreased dramatically as horses were slowly phased out as a means of transportation and farm work, the clout of union members continued for many years at American racetracks. For years, only IUJH members were allowed to shoe at most of the nation’s tracks.

If a trainer left a track with his horses in the middle of the night without paying his horseshoeing bill, the word would quickly spread. Moving to another racetrack, he would not be able to secure the services of any shoer until his horseshoeing bill was fully paid.

From 81 to 80,000 Union Members

In the early years of the 20th century, members of several worker and allied trade groups wanted to become members of the national AFL-CIO organization. Too expensive to join on their own, they needed to find a group with which to establish a partnership. Because the IUJH membership numbers were on the low end (most remaining members were racetrack shoers), these other groups found it to be a perfect union with whom to partner as a way to join the parent organization.

After toiling in relative anonymity for years, the horseshoers’ union couldn’t refuse this offer. As a result of this merger and the vastly increased total membership numbers, health care and other benefits became much cheaper for the remaining IUJH members living in the U.S. and Canada. From only having 81 horseshoers as union members in 2003, membership numbers have dramatically grown to around 80,000 dues-paying members trade and service worker members today.

— By Frank Lessiter, Editor