American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

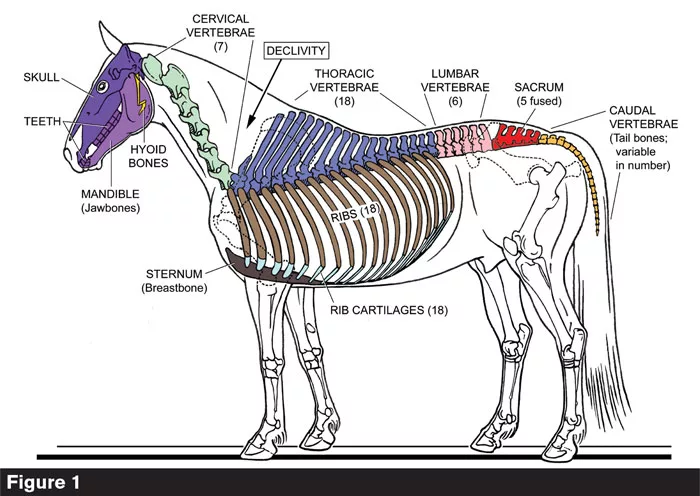

The equine axial skeleton (colors); uncolored parts belong to the appendicular skeleton. The spine consists of three arches (cervical, thoracico-lumbar, and caudal) which are joined at two declivities, at the base of the neck (marked) and at the base of the tail.

In part 5 of this series examining the equine hind limb, Dr. Deb Bennett explores hind limb reciprocation.

At the most fundamental level, reciprocation means energy exchange between linked parts of a biomechanical system.

We learned in the previous installment that the horse’s hind limb joints are tied by anatomical straps (in the form of tendons and muscles with tendinous cores) so flexion and extension must occur in coordination. This does not concern the stifle and hock joints only. From the top down, the joints that participate in reciprocation are the lumbo-sacral (L-S) that connects the lumbar spine to the sacrum, the hip socket, stifle, hock, fetlock and coffin joints (Figures 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8). In addition, there are joints in the horse’s hind limb, such as the sacro-iliac (S-I), the joints between the tibial and fibular tarsal bones and those between the splints and the cannon…