Biosecurity may feel exhausting and unnecessary, but infectious disease precautions should not be limited to a pandemic or other outbreak. Implementing a few standard cleaning measures and setting boundaries can prevent farriers from contributing to the spread of equine infectious diseases. Healthy, protected horses mean more consistent client appointments, and looking out for their well-being through basic biosecurity measures can build trust and respect between the farrier and owner.

Since the beginning of 2024, over 300 infectious disease cases have been confirmed by the Equine Disease Communications Center (EDCC) and over 1,400 horses exposed across the United States and Canada. When many of these cases have been diagnosed, other horses have already been exposed. According to the Fall 2020 Horse Report by the University of California, Davis’s Center for Equine Health, some of the most common infectious diseases to watch for are equine herpesvirus (EHV), equine influenza, salmonella, strangles, pigeon fever, West Nile virus and rhinitis virus. In foals, rotavirus, cryptosporidiosis, clostridium perfringens and Rhodococcus equi are also important to screen for.

Disease Transmission

Understanding how these diseases are spread can help prevent or minimize transmission. In addition to direct contact with the horse, infectious diseases can be spread through aerosols, indirect contact, oral transmission, vectors and wildlife. Aerosols include droplets from coughing, snorting or sneezing, which can become suspended in the air and transfer to another horse through contact with the eyes, nose or mouth. Diseases such as equine influenza and EHV are spread this way.

Though oral spread of disease requires a horse to lick or chew a contaminated bodily fluid or object, indirect contact is similar in that a living thing does not spread the pathogen. In this case, a horse only has to be exposed to things such as buckets, hoses, a farrier’s toolkit, clothing and vehicles to be at risk for an infectious disease. Strangles and EHV-1, which can lead to equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy, are transmitted this way.

While the spread of infectious disease through wildlife is largely out of the farrier’s control, vectors — or insects, such as mosquitoes and flies — that transmit West Nile and Eastern and Western equine encephalitis can be managed through fly spray. In the summer when it gets hot and humid, fly spray is important both for the horse and for the comfort of the farrier. However, it can get expensive when incorporating it into overhead costs. One strategy that Bob Smith, owner of the Pacific Coast Horseshoeing School, recommends is asking an owner to apply fly spray to their horses before a trim or shoeing. Another is to adjust a client’s fees to account for fly spray costs as a low-burden, high-reward biosecurity measure.

Another aspect of transmission to keep in mind is asymptomatic carriers. Research on asymptomatic carriers of strangles has shown that even after a horse recovers, it can spread the pathogen to other horses for at least 6 weeks.

“It's important to have both a preventative and response plan …”

“Up to 10% of horses that recover from an outbreak can become long-term silent shedders for months to years,” according to the Horse Report. “Stress, caused by transportation, illness, intense exercise, hospitalization, foaling, weaning, etc., can activate pathogen shedding by asymptomatic carriers, sometimes leading to disease outbreaks.”

Diseases such as EHV, influenza and equine infectious anemia can be transmitted this way, which is often why horses with equine infectious anemia, regardless of whether they’re symptomatic, will be permanently quarantined or euthanized.

Owner Perceptions & Preparedness

A survey of horse owners published in November 2023 by EDCC director Dr. Nat White and the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) Infectious Disease Committee found that 66.8% of owners have discussed infectious disease prevention other than vaccinations with their vet but only 54.2% have a plan in place.

When considering initiating biosecurity measures, signs of illness such as cough, nasal discharge, labored breathing and reduced appetite all prompt owners to take their horse’s temperature. The majority of owners will also isolate new resident horses and horses showing respiratory symptoms with a temperature of over 101.5 degrees, according to the survey.

When asked about the perception of risk level for horses that interact with non-resident horses (horses from different owners) during events or other competitions, 42.9% of respondents cited a moderately low risk, while 24% and 25.5% said slight risk and very low risk respectively. This may be because, according to owners, reasonable preventative measures are taken at many events such as vaccination entry requirements, restricting shared water and feed areas, disinfecting stalls between horses and providing hand washing stations.

However, for horses in contact with non-resident horses outside of an event setting, owners cited a variety of risk levels. 33.8% cited average risk, while 16.2% cited low risk and 14.3% cited an above-average risk. Because biosecurity measures taken with non-resident horses are often unknown, the risk is assumed based on the owner’s own preventative measures, assumptions and experience. The majority of owners implement some precautionary measures after being in contact with non-resident horses like hand washing, while a smaller percentage change clothes and/or footwear. However, only 2% avoid contact with other horses and 0.5% sanitize their equipment.

When assessing the risk of individuals who come in contact with an owner’s horse, 47.4% of respondents said that contact with a farrier increases the risk of the horse contracting an infectious disease. Closely following were visiting owners and veterinarians at 44.8% and 36.9% respectively.

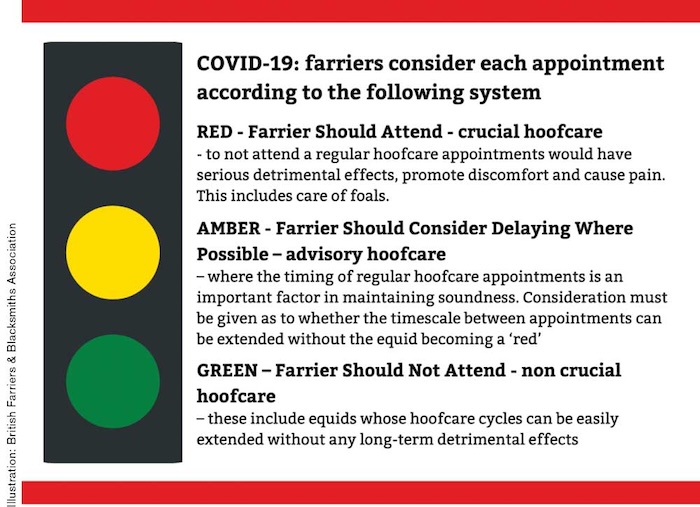

In 2020, the British Farriers & Blacksmiths Association divised the stoplight system to help farriers determine which hoof-care cases are most critical.

Biosecurity Measures

For a biosecurity strategy to be effective, the owner and farrier must both be committed, and it starts with communication. This means understanding and respecting owners’ precautionary measures and learning what to do should the farrier suspect an infectious disease. As with any human illness, by the time someone knows they’re sick, they’ve likely already exposed or infected others. For this reason, it’s important to not only have a preventative plan but a response plan.

For owners, prevention can be as simple as cleaning stalls, tools, cross-ties or anything around the horse after a farrier appointment or setting up a hand washing station for the farrier. Response plans can vary depending on a state’s biosecurity guidelines or owner’s protocol. However, isolation and regular cleaning help minimize the spread within a stable. Quarantine can also include foot baths outside the isolated stall and personal protective equipment such as gloves or disposable gowns to avoid having to change clothes between horses. If tending to a sick horse is unavoidable, working young to old and healthy to sick is the best way to mitigate the spread.

For the well-being of a farrier’s clients and business, it may be necessary to set boundaries with an owner. If the farrier is aware that a horse is sick before a visit, depending on the disease, the farrier’s and owner’s biosecurity measures and the farrier’s comfort level, postponing a visit or saving it for the end of the day can be the best course of action. If the farrier suspects the horse is sick on arrival, notify the owner and assess the risk. If adequate biosecurity measures aren’t available and the farrier can’t reasonably ensure the safety of the rest of the day’s clients, consider returning at a later date.

“After a horse has recovered, it can spread pathogens to other horses for at least 6 weeks …”

Whether there is an infectious disease outbreak or a single horse is sick, having biosecurity measures ready to implement when needed can protect an entire community’s horses. As a farrier, this can mean having spray bottles of disinfectant on hand and cleaning all tools and aprons before returning them to the rig to avoid contamination. Similarly, washing hands, arms and exposed skin will mitigate transmission, and a change of clothes or disposable gown can prevent the spread of strangles and EHV-1.

A disinfectant bath for footwear can help reduce the spread of contaminated debris on the stable floor. Using either a 1:10 ratio of bleach to water or accelerated hydrogen peroxide, shoes must be soaked rather than dipped for 10 or 5 minutes respectively. However, the Horse Report notes that foot baths are ineffective if there’s organic material on boots, such as manure, dirt, mud and plant material. Having a bristle brush nearby for quick cleaning can help avoid this.

Making a Decision

In addition to considering biosecurity measures, the health of the horse should also be taken into account. In 2020, the British Farriers and Blacksmiths Association created a stoplight system to help farriers prioritize hoof-care cases.

A red case delineates crucial hoof care, meaning that pushing back appointments would have serious detrimental effects on the horse and would promote discomfort and pain. An amber case is one where delaying care may be possible, but the timing of regular visits is important in maintaining soundness. Green means non-crucial hoof care, and shoeing cycles can be easily extended without negatively affecting the horse.

Though maintaining regular clients is important for a business owner, proper biosecurity measures will build trust and protect existing clients — including the most vulnerable, such as foals and older horses — from outbreaks. It can also protect humans from zoonotic diseases such as ringworm, salmonella, leptospirosis, Rhodococcus equi and MRSA.

Between January and June 2024, 154 cases of strangles have been confirmed, with over 600 horses exposed. Mitigating the spread of common infectious diseases like strangles means communicating a plan with owners before an outbreak happens, but it can also include simple, regular measures like hand washing, fly spray and disinfecting tools.

Takeaways

- Infectious diseases can be spread through aerosols, direct and indirect contact, orally and through vectors and wildlife to transmit pathogens that cause equine influenza, equine herpesvirus, salmonella, strangles and pigeon fever.

- Horse owners assess risk differently based on the biosecurity measures in place at events or their stables. Many owners allocate more risk to unknown biosecurity measures from outside visitors.

- Washing hands, disinfecting equipment, cleaning shoes and changing clothes are basic biosecurity measures farriers can implement in the event of an outbreak or to mitigate risk from a single sick horse.

- Assess hoof-care needs during an outbreak based on a stoplight system that determines which horses need the most critical care.

Related Content:

Biosecurity Protocols Limit Disruptions for Indiana Farrier During COVID-19 Pandemic

Farriers Encouraged to Implement Safety Practices During COVID-19