American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

Since 1992, “Shoeing for a Living” has been a regular feature in American Farriers Journal. Close to 150 farriers have been featured, each with unique and innovative ways to run their practice. Whether it’s a forging tip, an efficient way to set up your rig or a tried and true method to trimming difficult horses, there is always something to learn from your fellow farrier.

To celebrate AFJ’s 50th anniversary, we’ll bring you some of the most hard-hitting and practical tips for your business from previous “Shoeing for a Living” days.

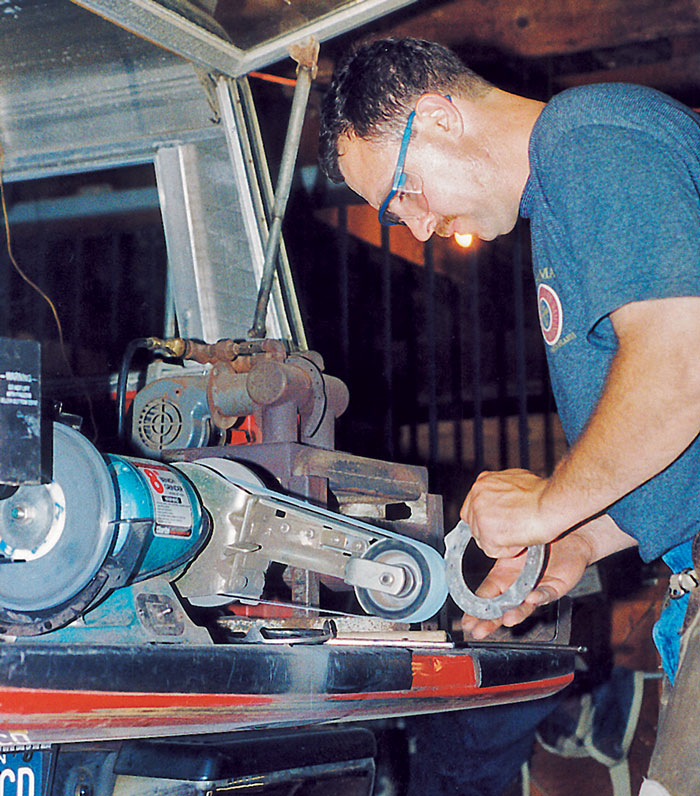

If there is a “trademark” to Michigan farrier Bill Ruh’s shoeing, it’s probably that he seats out the foot surface of most of the shoes he puts on horses to relieve sole pressure.

Attention to little things like that, Ruh says, are part of “a good, solid shoeing job.”

“That’s what I try for rather than any fancy shoeing,” he says.

Michigan farrier Bill Ruh values solid shoeing over “fancy” shoeing. Pat Tearney

One thing Ruh is adamant about is making sure each horse gets his full care and attention.

“A backyard horse that only gets ridden on Saturday or Sunday deserves just as good a shoeing job as an expensive show horse,” he says. “A horse is a horse.”

Handling the client’s outlook on their horse’s recovery during therapeutic hoof care often can be as much work, if not more, than helping the horse.

“That’s…