Seasoned shoers who have been in the industry for more than 30 years notice how communication among farriers has changed since they entered the profession. Decades ago, farriers wouldn’t readily share information with one another. During those times, a shoer would likely quit working if another shoer showed up at the barn, rather than give away any beneficial insight to observers.

Today, this reluctance has largely disappeared. Through clinics, local associations, general camaraderie and other venues, shoers are more likely to share knowledge for the good of the industry and the horses.

Work Together For A Common Cause

Jason Maki of Bryan, Texas, and farrier for Texas A&M University’s veterinary school says you need to always treat other farriers as if they have something to teach you. He advises you to surround yourself with farriers who know more than you about shoeing and the conduct of a professional. If you focus on self-improvement and acknowledge how much you have yet to learn, then your relationship with other shoers will grow.

“If you treat yourself and your career with respect, then it is second nature that you will treat other shoers with respect,” says Maki.

He finds the biggest mistake young shoeing school grads make is skipping an apprenticeship. By working with top farriers, you get to know clients and build a network of mentors. If you establish professional and personal relationships with other shoers, then you will be less likely to downplay someone. “In the long run, you will develop a professional demeanor,” he says.

Jim Jimenez of El Segundo, Calif., calls upon the Golden Rule and says you should treat other shoers the way you’d like to be treated. A veteran racetrack shoer, he says that spirit is necessary to keep the horses of that discipline going. For example, if a client’s horse springs a shoe and Jimenez isn’t present, another shoer will fix the problem. He would do the same if situations were reversed.

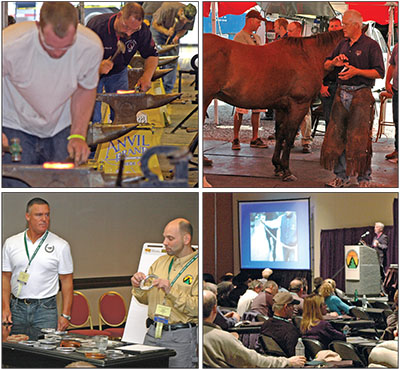

Your hoof-care education doesn’t end at the end of shoeing school or an apprenticeship. Part of a professional’s responsibility is to invest in continuing education. Farrier many educational options, from clinics at your local supply shop to forging competitions to large conferences, like the International Hoof-Care Summit.

“Working with animals like this, there is going to be a time when you are on the wrong side of a kick,” says Jimenez. “It is going to cost you a couple of days, so you would have to depend on other people to take care of your horses. Ultimately, you will return the favor. For the most part, we are an honest industry.”

Helpfulness isn’t the only courtesy to show another shoer. It also includes not speaking poorly of another’s work with others. Refuse to evaluate your competition’s work. When customers ask you to evaluate another farrier’s work, tell them that you don’t evaluate competitors’ work.

Jimenez says you should refrain from speaking about another shoer’s work because you don’t know what that other shoer was facing. Reflecting on his own work, Jimenez recalls occasions he would even question his thinking on the approach he previously took with a horse.

Longtime shoer Martin Kenny of Carthage, N.C., advises shoers to avoid the trap of criticizing other farriers,

especially with clients. If the client is critical of another farrier, Kenny finds that he or she eventually will turn on you.

His work often addresses issues that other farriers were unsuccessful in treating, so Kenny sometimes hears the negative comments. He tells the owner not to look backward and instead steers the conversation to a positive.

Brian Hull of Grand Valley, Ontario, believes you should never speak poorly of other shoers unless you are prepared to meet them face-to-face and tell him or her what you don’t like about their shoeing.

“You may feel differently about their shoeing after they explain to you why they shoe in such a way,” he says. “Remember, no horses’ hooves are exactly the same and no farrier shoes exactly the same as another farrier.”

In his experience, Hull finds that the type of farrier who criticizes his work is doing so as a tactic for going after his clients. More often than not, these farriers are young and never apprenticed with an experienced shoer to learn proper conduct. They typically undercut others on prices.

If he knows the other shoer, Hull will directly ask why he or she is going after his clients or unjustifiably criticizing his work.

“They deny that they would do such a thing,” says Hull. “I will explain to them that when word gets around to other farriers, the other farriers will tell their clients all about you.

“When you get on the bad side of a lot of established farriers, chances are you won’t get many good horses or barns to shoe at.”

While poaching clients is a short-term gain, in the end it can result in career suicide. Hull finds that these farriers will either change their attitudes or move out of the area.

“They are not well-regarded in the shoeing community,” he says. “They are not asked to many farrier get-togethers, don’t mix well with other shoers and have attitude problems.”

Not all criticism is an attempt to sabotage your practice. Well-intended critiques of your work delivered directly to you by a respected farrier can be valuable. Kenny says that even though there are exceptions, most farriers are willing to help and are not out to steal clients.

“Remember that when veteran farriers make comments to you about your work, it is not to belittle you but to lift you up,” says Kenny. “We’ve all been where you are today.”

Taking On Others’ Clients

Unless a potential client is a new horse owner with a recent acquisition, a hired farrier will replace another. If you exercise ethical business practices, don’t be ashamed when you are hired to replace a fellow shoer.

Kenny says farriers must always look to improve clientele. Remember, shoeing is a business.

“If one attempts to secure another farrier’s client in ethical manners, such as advertisements, personal contact or online, that is part of running a business and fair game,” explains Kenny. “However, if one says, ‘Hey, your present farrier is messing up your horses’ and behaves unethically, then that crosses the line.”

The North Carolina shoer reminds readers that farriers don’t own clients but instead are employed by clients to provide a service. Kenny advocates seeking new clients.

“The goal of any successful business is to draw work to yourself — and most of the time, that means drawing it from someone else!”

When a client inquires about hiring him to replace another farrier, Hull first asks himself if he knows the farrier. He thinks about the type of person and shoer the other farrier is. Hull will politely refuse the business if it is an associate, telling the potential client that he is not taking on new customers. If the client offers unsolicited

information concerning the other shoer, Hull won’t join in.

“If they tell me what problem they were having with their farrier, I may mention they should talk to the farrier, explain what the problem is and leave it at that,” says Hull.

Where you are at in your career will determine your approach for taking on new clients. Jimenez says he is at a point in his career where he is looking to shoe fewer horses, so he is less likely to take on a client looking for a replacement. He is one of the top-paid shoers in his area, so if he would take on a client, pricing won’t be a reason the client switched.

“I’ll ask what issue they have with the shoer,” says Jimenez. “If it is someone I respect, I tell them that I can’t do better, but I can do differently. If it is someone who is lacking the skills or doesn’t show up on time, I’ll talk to the other shoer about it.”

He adds that if you will take on the horse, make sure the client has paid the other shoer in full.

You’re Fired

Don’t overreact when you are fired. A client may let you go based on fickle or unreasonable reasons. However, don’t assume every time you are fired that it was unjustified. Evaluate your performance. What could you have done differently to satisfy that owner? Or what makes another farrier more appealing to the client?

Jason Maki believes that although it may vary to degrees, farriers who take the profession seriously operate by a code of ethics. Like Hull and Jimenez, he would contact a shoer he knows if that farrier’s client inquired about Maki’s service. When it is someone he doesn’t know, Maki embraces the free market nature of the industry.

“Every client I gained, someone else lost,” says Maki. “And every client I lost, someone gained.”

He warns against baring animosity against another shoer who replaces you. There are a million reasons why you lose clients. If you work on your farrier skills, your practice will have stability rather than the fickle clients who routinely fire farriers.