American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

In my previous article (May/June 2014), I described how the perimeter of the sole has greater rigidity because of its attachment to the hoof wall, and provides a “ledge” for the solar border of P3 to rest on (Figure 1).

In some circumstances, deformation of the hoof wall and/or increased forces on P3 reduces the effectiveness of the ledge and the support it provides is either reduced or lost (Figure 2).

In this follow-up, I discuss this further with images to illustrate points.

Distortion or deviation of the distal wall can cause the border of P3 to rest on more flexible sole axial to (inside) the ledge. Figures 3a and 3b are radiographs of the left and right forefeet of a Quarter Horse that show this.

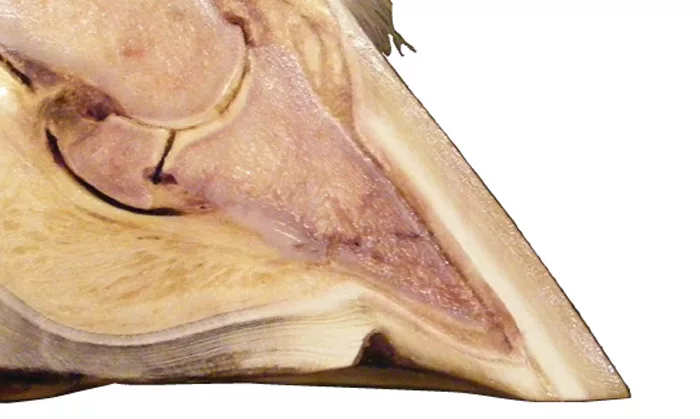

The loss of support of the ledge is most commonly and obviously seen in the chronic laminitis case, where separation of the laminae, disruption of the white line, dorsal wall deviation and rotation of P3 leave the bone’s tip, pressing directly on the sole (Figure 4). How successful or effective we are at treating acute laminitis cases will have a significant bearing on whether acute cases progress to the chronic state.

With low-grade laminitis caused by insulin resistance (IR), there is lengthening of the laminae and can be disruption of the white line, which weaken the support. The effect of these changes is made worse if the IR horse is overweight (Figure 5…