American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Anatomy and Common Disorders of the Horse

“For something so small, equivalent in size to our little finger, the navicular bone can render a 1,000 pound, finely-tuned equine athlete into a pasture pet — permanently,” explains Dallas O. Goble, DVM, DACVS, former Director of Equine Clinics at the University of Tennessee and current head veterinarian for the Budweiser Clydesdale National Herd Health Program.

“As professionals in the field, you no doubt know, having had the misfortune to treat such a horse on occasion,” says the Strawberry Plains, Tenn., equine veterinarian. It seems that more clients’ horses experience navicular disease than ever before. Goble believes that farriers must understand the basic points of this crippling disease. By following his advice, you can give your clients a working knowledge of how to prevent, or at least manage, the damage before it’s too late.

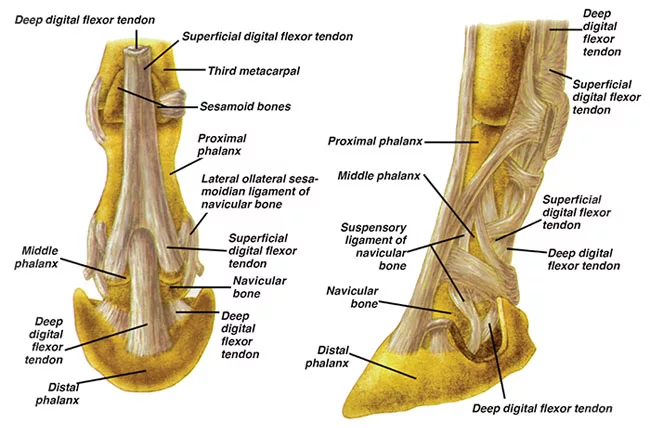

Of major importance to mobility of the limbs, Goble says the navicular bone “lays the groundwork of movement by serving as a conduit between the coffin bone and the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT).” Defining it as a sesamoid bone (similar in nature to the sesamoid bones located behind the fetlock), it is positioned behind the coffin bone and below the small pastern bone, with the DDFT running underneath.

“As the navicular bone articulates with the coffin joint, or distal interphalangeal joint, on its anterior (front) surface to provide a smooth caudal (posterior) surface over which the deep flexor tendon glides,” says Goble. He further illustrates its impact by pointing to the…