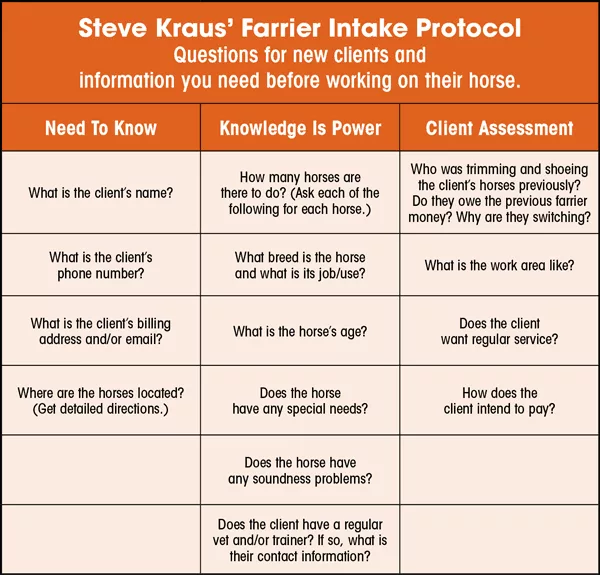

Pictured above: Steve Kraus' Farrier Intake Protocol: questions for new clients and information you need before working on their horse.

Building relationships with clients and knowing when to let them go may sound as easy as saying hello and goodbye, but there are a few things farriers should keep in mind when developing and ending client relationships that can make everything go a little more smoothly.

When taking on a new client, it is all about asking the right questions up front and getting enough information to allow you to be prepared to execute the job the first time. Asking the right questions will also help you to know the trustworthy clients from the unreliable or even dangerous ones.

As time goes by and you gain a reputation and prestige in your area, you may find that you have more business than you did when you first started out and were starving for any client who would call. At this point, you can begin looking at which clients you may no longer need or, more likely, want.

When you’re ready to end a client relationship, don’t just stop answering the phone or not show up to an appointment. Take a more professional approach and end the relationship in a way that will leave both your reputation and the reputation of the farrier industry intact.

Follow this advice from veteran farriers on how to hire and fire clients.

Hiring Clients

Finding and hiring clients is one of the most essential jobs a farrier has to do to get their practice off the ground. However, it’s not as easy as picking up the phone and running straight to the barn. First, you must ask your prospective new client a few questions to help you be prepared for the job.

Avoid being underprepared when working with a new client by getting in-depth information on the horses. Don't forget to ask for the basics.

Tell new clients what you charge and ask how they intend to pay before accepting a job.

When firing a client, explain the situation to them coolly and professionally. Never just ignore clients.

Steve Kraus, head of farrier services and farrier school instructor at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine in Ithaca, N.Y., teaches his farrier students to ask the right questions and gather the right information when a possible new client inquires for your services.

Kraus has a few different levels of information that farriers should gather. First is the “need to know” information, which is absolutely essential to being able to get to the work site and get the job done. The next tier of questions are “knowledge is power” questions that will provide information to help farriers be prepared for the job and know exactly what they are expected to do. The final set of questions is “client assessment” based and will give you an idea of the reliability of the client.

Asking the right questions up front can save you headaches later.

“I learned to ask these questions through experience,” says the Hall Of Fame farrier. “There have been many times when I showed up to shoe four horses and it sounded like a good client and then you see the run-down place they expect you to work in and they tell you they can’t pay until next month.”

Grade Your Clients

Bob Smith of Pacific Horseshoeing School uses a letter grade system to help discharge clients when the time comes. Here is how he grades:

A: Clients who pay immediately and schedule regularly. They care about your safety and comfort and they provide the facility to shoe. They with you when you increase your prices. The horse has good feet and will stand quietly.

B: Clients who care about your safety and comfort, but are unable to provide for it.They're good people and they'll pay you, but they falter when prices are raised. The shoeing conditions are on the side of the barn, on a bit of dirt or gravel where it's hard to set up the horse on its angles and stuff. The horse might have bad feet, but will stand, although not perfectly.

C: Clients who care about the horse first and you second. They have a poor shoeing environment and you must bill them because they won't pay right away. They also won't stick to a regular schedule. The horse doesn't want to cooperate or has poor conformation. Shoes are difficult to keep on.

D: Clients who must be tracked down to pay or write bad checks. They care about the horse first and you second. They'll bring three or four horses and demand that you charge the same for each one. The working conditions are poor. They call after they've gone 12 or 13 weeks without getting the horses done and call you up on a Thursday night and want the horses shod on Friday because they will be trail riding on Saturday. The horse is dangerous and ill mannered.

Getting The Basics

Kraus’ “need to know” questions include getting the client’s name, phone number, billing address and/or email and getting detailed directions to where the horses are located — the basics.

“You need to start out with the simple things, which are things that you really need to have to do the job. When I started shoeing horses, there wasn’t GPS or smartphones you could use to find directions,” Kraus says. “Even today, some of the GPS and apps still won’t be able to get you where you want to go, so getting good directions is very useful.”

Remembering to ask the basic questions is especially important for beginning farriers to keep in mind, Kraus says.

“Beginning farriers are so excited that the phone is even ringing that they might make an appointment without asking any questions,” he says. “Then they’ll go there and sometimes they’re not prepared for what they’re going to get into. And not being prepared wastes the time of both you and the client.”

Aside from good directions, Kraus also stresses the importance of asking a new client for their phone number.

“You need at least a phone number or a way to contact the client should something come up,” Kraus says. “Horseshoers are notorious for missing appointments and not letting the client know. In today’s world where everyone has a cell phone, there’s no excuse for that kind of behavior.”

Tips For Finding Clients

Finding clients can be trying when embarking on your hoof-care business. It’s a challenge that Texas farrier Brody White knows all too well.

After enduring the growing pains of building a client base for his fledgling farriery practice, White launched an app with California farrier Trent Thompson that aims to make it easier for horse owners to find farriers.

“Equine United is a geolocational directory for all of the horse’s needs — farriers, dentists, chiropractors, vets, transportation, trainers and groomers,” White explains. “All the user has to do is open the app and it gives a map of all the providers in that area. They just click on the provider’s icon and it will list the phone number, star rating, etc. The app also allows users to essentially post a want ad for the services they need. Providers in their area can open the app and see if anyone needs work to be done. It will help farriers get business instead of waiting for it to come to them.”

More than 1,700 providers — 900 of whom are farriers — are listed on the app, which is free for the horse owner. To be a listed provider, visit EquineUnited.com and click on the provider link. After filling out the online forms, your information will be listed for $3.99 a month.

Fellow Texas farrier Ralph Hampton regularly uses social media for educational and marketing purposes.

“Facebook is wonderful,” he says. “It can be your friend, but you have to work it a certain way. I see the standard stuff, like a business card with Ol’ Johnny’s phone number and a slogan — ‘I’m the best in the west and better than the rest,’ that sort of stuff. I just cringe. It just hurts me, because it doesn’t work.”

Hampton has found success in developing client leads by writing short posts — less than 500 words — for horse owner groups and his clients.

“Since I’ve been doing this,” he says, “I’ve had all the leads that I could want.”

The key to Hampton’s posts is using common sense terms with which the horse owner can relate.

“Every farrier should know what a broken back HP axis is, but if you start spitting out those terms, clients will look at you like you just sprouted a head,” he says. “They have no idea what that means. But, if you tell them the horse has crushed heels, they’ll say, ‘Oh yeah, I see that.’”

Horse trading websites have the potential to generate client leads, as well.

“Most of them offer a farrier section,” he says. “They send me one to six leads a day. All you have to do is call people and let them know you’re in their area. They’re not going to know you from Adam, so I let them know that they can visit my Facebook page to take a look at photos of my work. When they do that, they can’t get to the phone quick enough to call back.”

Being Prepared

After you have the basics down, Kraus suggests getting a little more detail on the horse or horses you will be expected to work with. You might be able to get the job done without this information on the first shoeing, but you will save yourself time and money by being prepared with the proper tools and supplies the first time.

Ask a new client how many horses they have for you to work on, the breed of horse, its age and whether it has any special needs or soundness problems, as well as what the horse’s job or use is.

“Will you be shoeing hunters or barrel racing horses?” Kraus asks. “This might determine whether you can even take the client. If you’re not prepared or don’t have the experience or knowledge to shoe that type of horse, you need to know beforehand. You may need to decline that client or find a way to become better prepared.”

He cites a case with a horseshoeing school graduate.

“Many years ago, I had a fellow come up to me who had just graduated from a very good school where they worked on a lot of field hunter horses and that is what he knew how to shoe well,” Kraus recalls. “But then his first client happened to be people with barrel racing horses and he wasn’t prepared for that. He lost shoes like crazy because he shod them like they were field hunters.

“You can’t treat shoeing a horse as a generic thing. There may be some horses that can get by with more generic shoeing, but as you get into high performance horses, you need to have the right shoes and training to succeed.”

Knowing the age of the horse will help you determine how much time you will need to shoe or trim it.

“It’s nice to know the approximate age of the horse,” he says. “There’s a difference between shoeing a very young horse and a very old horse, as they can take more time to work with.”

At this point, it’s also appropriate to ask whether the horse has any behavioral problems, as Kraus says those horses may also take more time.

“If you know a horse has a behavioral problem or has never been shod before, you’ll need to be prepared to handle it,” he says. “The owner may not tell you up-front that the horse is unruly because they don’t want to scare you away. But they probably won’t lie to you if you ask them the question directly.”

Kraus also suggests getting specific information on the services the new client expects you to provide for each horse. Do they want all of their horses shod, or just trimmed?

“You need to get specific on what needs to be done before the job,” he says. “That way you have the materials you will need and leave time to do everything you need to do.”

He also asks the new client whether there is a trainer or vet they work with.

“You want to know whether there is a vet you can speak with if there are any special soundness problems,” he says. “This is very useful information, but you don’t need to get too involved with the details on this right away.”

6 Questions To Ask Before Hiring A Client

Like Steve Kraus, Ridgeland, Wis., farrier Justin Mundt has established a questionnaire that he calls his “Red Velvet Rope Policy.” Mundt asks six open-ended questions each time a potential client contacts him, which he uses as a vetting process.

1. Who do you currently use for a farrier?

“This question is gold!” Mundt says. “Simply ask the question and let them answer without interruption. You’ll learn valuable information, such as: whether the farrier fired the client, what they don’t like/used to like, how long they had the farrier, etc.”

2. When was the last time the horses were worked on?

“This lets you know how much they value the horse,” he says, “and whether they will be a regular client.”

3. How well do the horses behave for the farrier?

“If a horse doesn’t behave, I don’t work on them,” Mundt says. “It’s best to know this up front.”

4. Do you prefer to set up a schedule or do you call when you think the horse needs to be done?

“I state this question with a tone of voice that conveys that it’s OK if they just call to set up the appointment when they want,” he says. “If they take that road, I don’t work with them.”

5. What type of facility do you have, and where does the farrier normally work with your horse?

“This lets you know whether they have shelter from the elements or a hard, flat surface to work on,” Mundt says. “Or, whether you’ll be tying the horse to a barbed wire fence while shoeing in liquid manure under the hot sun.”

6. How have you paid your farrier in the past — cash, check or have him/her bill you?

“This lets me know whether they will take my services seriously,” he says. “Pay close attention to this one.”

Over the years, Mundt has developed a script that he conveys to the potential client to ensure nothing is left to chance.

“OK, that sounds great. I like to be transparent with my clients, so that way there are no surprises, and everyone knows what’s expected up front and no surprises.

“I require a flat, level, well-lit place that’s out of the elements and free from distractions such as chickens, ducks, geese, screaming kids, barking dogs or anything hazardous to me or the work I’m performing while working on your horse. This means a barn alley or garage floor free of hazards, etc.

“I require payment in cash for new customers for the first 3 appointments until we establish a working relationship. Once you become a regular client, then I’ll accept a check. However, that privilege is only for regular clients, since I’ve been burned in the past.

“As far as the behavior of the horses, I don’t wrestle, train, work on, train or get kicked around by a horse that isn’t trained to behave for the farrier. If the horse doesn’t stand well and behave to have its feet worked on, I simply just walk away.

“I say this because I’ve had people say otherwise and they think since I’ve driven that whole way that I’ll just work on the horse anyway. I won’t. If they don’t behave, I walk away from that horse.

“If you are able to keep a 6-week (or whatever you want) schedule with your horses, I’d be more than happy to accept you as a customer.”

Assessing The Client

Not every horse owner has an immaculate barn, and, as Kraus puts it, not every horse owner can truly afford his or her horse. To determine whether a new client is going to be reliable and provide safe working conditions, Kraus recommends asking the prospective new client up front about what the work area is like, how the client intends to pay for service and whether they are looking for regular service.

“You need to know if the horse owner has a decent place to work,” he says. “Will you be working in a barn or out in a corral? Am I going to be able to get my truck to the barn or is this barn in the middle of a swampy pasture? Is it safe? Am I going to have a hard time working there?

“Be prepared and know before you accept the job how you’re going to handle these situations. If I can’t get my truck to the horses and I’m still going to work on them, maybe I need to get a stall jack.”

Kraus says farriers also need to let the new client know what they charge before accepting the job.

“There are many different types of shoes and some cost a lot more than others,” he says. “If we’re shoeing warmbloods, that’s not the same price as shoeing a little trail horse. Once you know what the client wants you to do on each of their horses, let the client know what you charge and then find out how they intend to pay. That’s an important step because some people haven’t really thought about that when they call.”

If you aren’t careful to set up a method of payment beforehand, Kraus says, the client may not be ready to pay immediately after service.

“And then maybe the money never comes,” he says. “These things happen, so tell the client up front what the work will cost and what methods of payment you accept — credit card, cash or checks. Getting it all straightened out ahead of time will save you a lot of confusion and difficulty down the road.”

When a new client gets hung up on what you quote for the price or argues about it, Kraus says this can be a red flag that this client could be difficult to work with.

The last thing Kraus asks new clients is whether they are looking for regular farrier service.

“I only like to take on new clients who are going to have regular service. Not someone who has a trail ride this weekend and the horses really need to be trimmed and they just want whichever farrier can get there the quickest,” Kraus says. “It can be hard to tack people down on whether they want regular service before you start shoeing for them, but it doesn’t hurt to ask the question.”

Asking new clients the right questions at the beginning of the conversation can help pave the way for a successful farrier-client relationship.

“If you have all of this information at your disposal, you can make a good assessment of how you’re going to work on the horses,” Kraus says. “You won’t be surprised when you first arrive and you won’t be full of questions on what you’re expected to do. Instead, you can focus on getting the horse trimmed and/or shod properly. You will have the right shoes in your truck and the right amount of time to get the job done. You will succeed because success comes from preparation.”

Firing Clients

As your farrier practice and clientele grow, so can the quality of clients you work with. What makes a quality client may be different for one farrier than it is for another. The same can be said of what makes a bad client, though there are a few areas that can be red flags. These include ill-mannered horses, dangerous work area, poor or late pay and uncooperative or micromanaging clients.

There are many schools of thought on how to peacefully end a relationship with a client, but most agree that you don’t want to burn any bridges and leave in a screaming match, nor can you just stop showing up for appointments with that client. Bob Smith, owner of Pacific Coast Horseshoeing School, uses a grading system when determining to discharge clients (see chart above).

“In this industry, we gain a reputation for not showing up and not answering our phones,” says the Hall Of Fame farrier. “I think that’s the way many farriers fire their clients. They want to avoid conflict, so they just ignore them, but that gives all farriers a horrible reputation. It’s a disservice to all farriers because clients will begin thinking there is something wrong with farriers and not with their horses or their pay.

“Fire clients for cause, professionally and proactively,” Smith says. “Never fire a client in anger.”