Farrier Takeaways

- Farriers must understand what’s contained in radiographs, otherwise veterinarians are simply telling you what to do.

- Farriers must develop their ability to read the foot to determine how much should be removed.

Quality radiographs are pivotal for veterinarians and farriers when providing a horse and its owner proper therapeutic hoof care.

Flaws in any element of recording the images will render them detrimental. As veterinary radiologist Peter Suter once said, “At best, poor radiographs are totally useless, and at worst, they are totally misleading.”

Brent Barrett, an Ocala, Fla., veterinarian and Certified Journeyman Farrier, told attendees during a clinic at Centaur Forge in Burlington, Wis., that achieving a quality radiograph relies on understanding the information contained within the image, the technique used to capture it and the assessment of soft tissue parameters.

Understanding Radiographs

Why is it important for veterinarians and farriers to understand radiographs? They assist in comprehending the makeup of the foot we’re addressing, establish a link between external and internal anatomy and improve veterinarian-farrier relations.

Know what you are looking at. Radiographs assist in achieving a diagnosis, developing a protocol and allowing vets and farriers to assess the work.

“Is the foot better?” he says. “Has sole mass improved? Has the palmar/plantar angle [PA] dropped or increased? It allows you to assess your worth.”

External and internal links. Like many veterinarians starting out, Barrett hadn’t performed much therapeutic work, but had shod a fair amount of straightforward horses. His awareness of the connections between the external and internal anatomy heightened when the veterinary practice he worked for performed pre-purchase exams on the hunter/jumper show horse circuit.

“I was used to thinking about the foot in terms of things that touched my hands and tools — frog, sole, walls, bars, those sorts of things,” he recalls. “Looking at a large number of radiographs of feet and correlating the pathologies and lamenesses started forming a bridge about how what I was touching affects the soft tissue structures.”

Vet-farrier relations. If a farrier wants to perform therapeutic work, it’s beneficial to grasp the images on the screen.

“The veterinarian needs to know that you understand it,” he says. “Otherwise, they are simply telling you what to do. I hope when I meet with the farrier that they have enough knowledge that we can have an active conversation about what’s wrong and the direction we’re going to go.”

Radiograph Technique

Shooting X-rays isn’t as simple as pointing the beam at the hoof and snapping an image. Barrett follows a list of tasks that he accomplishes to capture a clean radiograph.

1. Clean the feet. Debris on the hoof wall and in the bottom of the foot can provide misleading information.

2. Even feet placement on blocks. “Does it make a big difference if one foot is on a block and the other isn’t?” he asks. “I haven’t studied it much, but it’s just a good habit. You don’t want to guess if the subtle changes is an issue or not. You don’t want to blame it on them being shifted because of some imbalance being on blocks.”

3. Horse stands square and head/neck straight. A horse that stands square and straight ensures that its posture is true. Otherwise, incorrect information, such as uneven joint spacing, could be captured.

4. Mark coronary band and dorsal hoof wall. “I mark the coronary band with barium paste,” Barrett says. “I start my mark where you can just feel over the ledge of the coronary band and the hoof wall. If you’re off by 2 or 3 millimeters on a laminitic horse, that may be crucial because you need to know if the horse is sinking.”

5. Mark tip of frog. “If you want an internal to external reference point to determine where to put breakover or where the tip of the coffin bone is, the tip of the frog is a good place to go,” he suggests. “The veterinarian can measure that for you if you’re not together or you don’t have access to the radiographs.”

6. Beam location. When radiographs to assess balance are necessary, Barrett encourages the farrier to speak up.

“You have the right to say,” he says, “‘Can we do this a little differently?’”

To achieve this, the center of the X-ray beam should be focused on the ground surface of the hoof.

“The X-ray beam is like a shotgun,” he explains. “It comes out and spreads. Whatever you’re looking at, whether it’s a joint or the foot balance, you want the beam passing straight through it.”

7. Plate placement. Barrett wants the plate as close to the foot as possible to reduce magnification.

8. Block markers. Barrett wants to see only one coffin bone wing, one branch of the shoe (Figure 1a) or the correct block marker. Since he made his blocks, Barrett placed four screws within them.

Proper beam location will result in radiographs that show one coffin bone wing and one horseshoe branch. Images: Dr. Brent Barrett

“The screws are set at the same plane,” he says. “When I see two screws instead of four, I know I’ve shot at the top surface of the block, the foot surface, or the ground surface of the shoe.”

When an image captures two coffin bone wings (Figure 1b), one of three things could be occurring.

An indication that the beam is passing at an incorrect location is when two coffin bone wings are visible.

“You can have an asymmetrical coffin bone within a foot that’s actually balanced,” Barrett says. “You might have a medial-lateral imbalance. Or your beam is passing at too much of an angle underneath the bottom of the coffin bone.”

When two coffin bone wings and four screws are visible, as seen in Figure 1b, anatomical accuracy is in doubt.

“How do we measure sole depth?” he asks. “If the sole is superimposed by a wing of the shoe, we don’t know where it ends. If you’re measuring the PA, a lot of times it will be different from one wing vs. the other. So, it’s crucial to get the soft tissue parameters on the bottom of the foot flat.”

Soft Tissue Parameters

Although a radiograph is an effective tool to map out the parameters of the foot’s soft tissues, farriers must develop their ability to read the foot.

“The radiograph will tell you how much foot there is, but the foot will tell you how much can come off,” Barrett says. “You still have to be able to read the foot to say that another eighth or sixteenth of an inch can be removed, which may be the difference between a happy horse or one that’s too short. New Mexico farrier Craig Trnka got it in my head years ago that if you’re going to err on leaving a horse a little too long or a little short, my career will probably go better if I leave the horse just a little too long. You can always come back and take it later.”

Barrett credits Dr. Ric Redden with identifying the following soft tissue parameters — the hoof capsule/lamellar zone (HL), sole depth (SD), palmar/plantar angle (PA), digital breakover (DB), digital toe length (DTL), center of articulation (COA), medial-lateral balance, coronary band/extensor process (CE) and hoof pastern axis (HPA).

Hoof capsule/lamellar zone. When measuring HL (Figure 2), Barrett begins at the dorsal face of the coffin bone to the outer portion of the hoof wall. The average horse is 16-18 mm. This is where the barium paste comes in handy to accurately identify the outer portion of the hoof wall. The burnout on the outer edge of the wall may vary with technique making it challenging to determine exactly where the wall ends.

The average horse has 16-18 mm of hoof capsule/lamellar zone.

“If you’re seeing a horse that you think has laminitis for the first time and it’s 16 over 22, then you have to figure out what it has,” he says. “Does it have acute or chronic laminitis, dorsal hoof wall distortion, or something else? If the HL zone is 22 over 22, there’s a pretty good chance that horse is sinking.”

Sole depth. There are two main areas that Barrett focuses on in hoof care — bringing the foot underneath the bony column and building sole depth (Figure 3).

Sole depth is measured at the tip of the coffin bone.

“Almost all of the horses I work on,” he says, “don’t have enough of it.”

Sole depth is usually measured at the tip of the coffin bone and ranges between 8-18 mm, depending on breed and conformation. The measurement to the ground surface includes the cup and represents the amount of arch in the foot.

“Sometimes it can be difficult to determine if there are layers of exfoliated sole that haven’t been removed,” Barrett says. “That’s not functional sole depth.”

Palmar/plantar angle. The angle of the ventral aspect of P3 (Figure 4) is measured to the weight-bearing surface of the foot. The average is 3-6 degrees, while 0-10 degrees might be considered acceptable, depending on hoof conformation.

The angle of the ventral aspect of the coffin bone is measured to the weight-bearing surface of the foot.

“If you have an appliance with a wedge in it,” he says, “you will probably want to measure the PA to the wedge where the foot and pad or the foot and the shoe interact.”

When a horse has osteomyelitis with reabsorption at the tip of the coffin bone, Barrett suggests measuring it off the caudal aspect of the coffin bone.

While PA is not the end all, he says, it’s gaining importance among veterinarians.

“It’s one of the things we’re starting to look at more,” Barrett says. “We’re finding that many horses with bilateral proximal suspensory injuries in the hind limb have negative plantar angles.

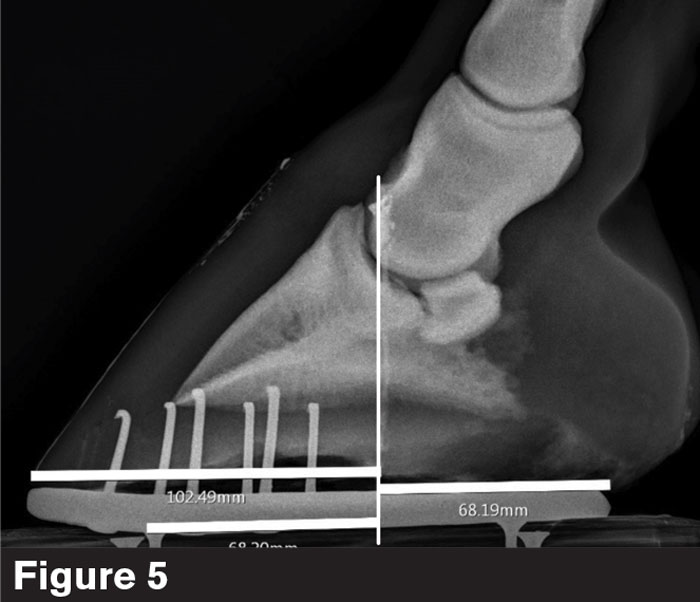

Center of articulation. COA (Figure 5) is roughly located at the widest point of the foot and a thumb’s width behind the anterior coronary band.

The center of articulation is roughly located at the widest point of the foot and a thumb’s width behind the anterior coronary band.

“If you look at Figure 5, it it’s flat shod it has 102 mm, if it’s flat shod, in the caudal half and 68 mm in the caudle half,” Barrett says. “I don’t want to argue about the difference of 4 or 8 mm, but when we’re off by as much as 30 mm either way out of balance, we need to get this horse closer in balance.”

Ideally, Barrett’s goal is to be close to 50/50 balance around the center of the coffin bone at the end of a shoeing cycle.

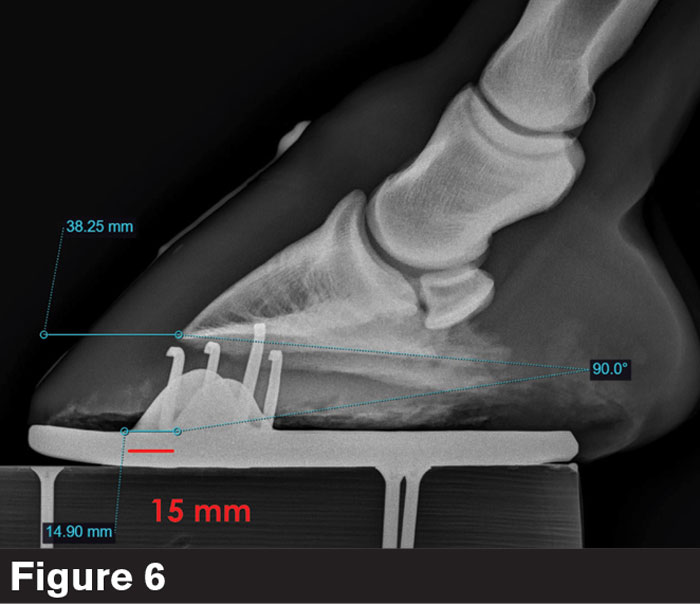

Digital breakover. DB is the distance from the cranial tip of the coffin bone to the point where the foot or shoe is no longer in contact with the ground (Figure 6). The ideal number varies with hoof conformation, pathology and goals.

Digital breakover is the distance from the cranial tip of the coffin bone to the point where the foot or shoe is no longer in contact with the ground.

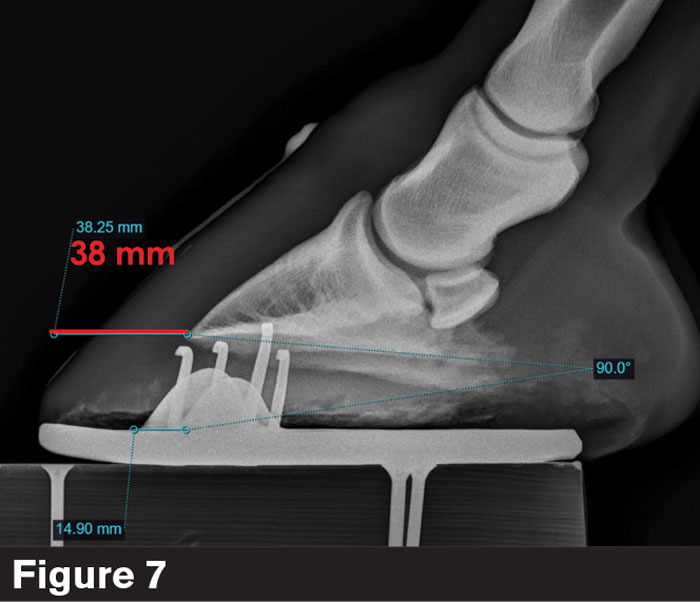

Digital toe length. Farriers might not be familiar with DTL since Barrett created it to quantify when a toe is too long. It’s the distance from the tip of P3 to the most cranial portion of the shoe or foot (Figure 7). When the shoe or foot is flat, the DB and DTL are the same. The ideal length seems to be roughly 25-30 mm after the trim.

Digital toe length is the distance from the tip of the coffin bone to the most cranial portion of the shoe or foot.

“When a veterinarian says the horse’s toe is too long and the farrier says that more can’t be taken off, both are right,” he says. “It’s helped me determine where I place my shoe.”

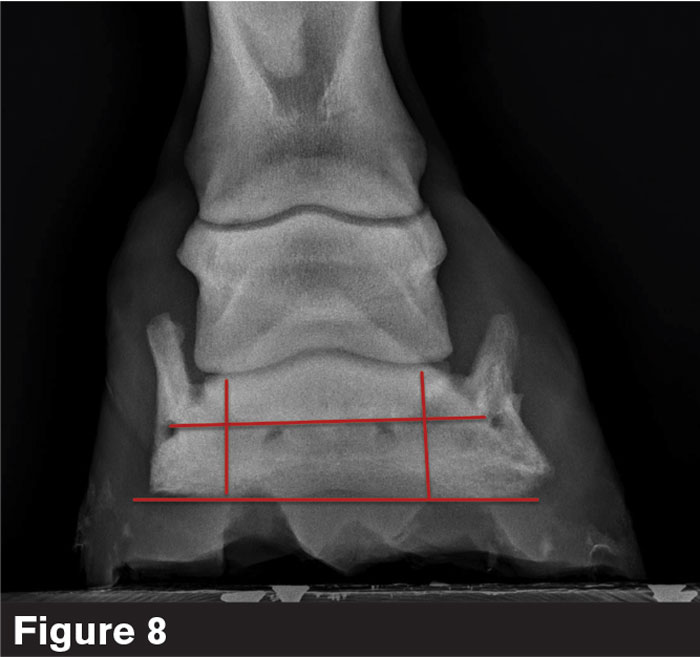

Medial-lateral balance. Barrett concedes that he struggles more with medial-lateral balance since he has access to radiographs (Figure 8).

There are many ways to determine how to balance a foot. Dr. Brent Barrett advises farriers to avoid using one as the deciding factor.

“There are so many ways to look at medial-lateral balance,” he says, “and everybody has a different opinion.”

Among them include the ventral surface of P3 parallel to the ground, the vascular foramen parallel to the ground, the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint spacing, level coronary band, amount of sole depth under each wing of P3. Then, you have to compare the radiograph to what you see in the actual foot and decide what is balance.

“Don’t use one parameter for deciding how to balance a foot,” Barrett says. “I have horses that have three things telling me one thing and three things telling me another. If there are too many ambiguities on the radiograph, I read what the foot tells me.”

Coronary band-extensor process. The CE is the distance from the coronary band to the extensor process (Figure 9). There can be a variance of 5-20 mm.

The coronary band-extensor process is the distance from the coronary band to the extensor process. There can be a variance of 5-20 mm.

“This is a good determination for laminitic sinkers,” he says. “I’ve had horses that are sinking but the number barely changes. It’s tough to determine a baseline pathologic number. One horse might be normal at 8, while another might be normal at 18. You have to use it as a reference throughout the serial radiographs.”

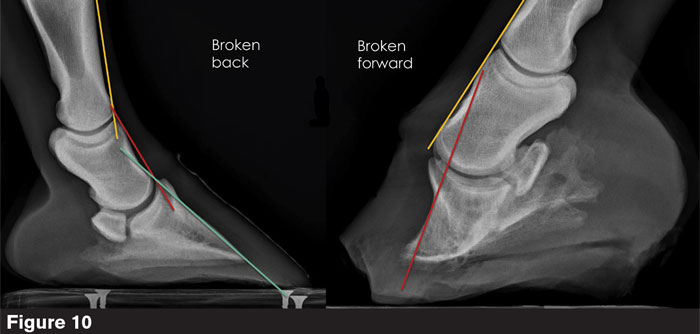

Hoof-pastern axis. Ideally, the three bones in a horse’s HPA (Figure 10) should line up; however, it’s not necessarily practical on many horses, Barrett says.

While the three bones in a horse’s hoof-pastern axis should line up, it’s not always practical on many of them.

“We should get as close as possible,” he says. “Horses that are chronically lame, foot sore, sore coffin joints, tendon structures, will probably benefit from getting the alignment a little closer together.”

A good example is the broken forward foot in Figure 10. How much foot should be removed to align the HPA?

“If you drop its heels too much, the horse will not be happy,” Barrett says. “We have to figure out what can we sort of fix, what can we fix, and what do we have to manage the best we can? Sometimes we just have to say, ‘I think this is the best we’re going to get on this horse.’”